The Intermediary Relending Program (IRP) was first enacted in the 1980s and has had remarkable success in strengthening rural communities through investment in local projects. Because loan capital is revolved several times over the course of an IRP loan to an intermediary, USDA estimates that every $100,000 in IRP loan funds leads to the creation of 76.5 jobs by the entities that receive funding from the IRP intermediaries. Further, despite significant decreases in funding over the past decade, the IRP is credited with assisting an estimated 9,000 rural business across the country.

What is the IRP?

The Intermediary Relending Program, or IRP, provides low-interest loans to local intermediaries that in turn re-lend the funds to businesses and for community development projects in rural areas. Today it is administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) by the National Rural Business Cooperative Services (RBCS). Non-profits, cooperatives, federally recognized tribes, and public bodies are eligible to serve as intermediary lenders under the IRP. Using the funds, the intermediaries create revolving loan funds (RLF).

In general, an RLF is a pool of public- and private-sector funds that recycles money as loans are repaid. Lenders, which can be state or local government agencies and nonprofit organizations structured to make loans, receive funds from a number of federal departments, including USDA. The lenders in turn provide loans to local groups within their communities, which use the funds for economic development and business growth. Frequently, the communities in which RLFs are used have no other affordable credit options.

What is the Background of the IRP?

The IRP has its roots in the War on Poverty. The Economic Opportunity Act (PL 88-452) included a “Special Impact Programs to Combat Poverty in Rural Areas,” and an authorization for loans to “raise and maintain the income and living standards of low income rural families and migrants agricultural employees and their families.”

While Congress initially authorized this program in 1967 and provided some $70 million in appropriations a few years later, the Rural Development Loan Fund (RDLF) never got off the ground. Through the 1970’s, OEO and its successor, the Community Services Administration (CSA), refused to make the money available. Finally, a lawsuit forced the Administration’s hand, and the Carter Administration was ordered to obligate the money. In 1980 and 1981, approximately $35 million in RDLF loans was made to a several Community Development Corporations (CDCs).

Those first loans had 30-year terms and carried an interest rate of 1% for the first five years of the loans. After the first five years, the interest rate rose to the market rate in effect when the loan was made. In the early 1980’s market interest rate were in the double digits.

In 1981, Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (PL97-35). That bill effectively repealed the Economic Opportunity Act, and created a successor agency within Health & Human Services (HHS) – the Office of Community Services (OCS), which established a block grant for grants to community action agencies and a discretionary program for grants to CDCs and rural water technical assistance. The legislation also established a development loan fund that served as the successor authorization for the RDLF.

Under the Reagan Administration, OCS made one more round of IRP loans in 1983 – at 5% interest– to about a dozen CDCs.

The changing interest rate environment of the mid-1980’s put the CDCs with the original RDLF loans in a precarious situation. The interest rate for the RDLF loans on their books would soon increase to higher than 10%. At the same time, the economic downturn was forcing rates lower than the RDLF note rate.

After negotiations with HHS to revise interest rates collapsed, the CDCs persuaded Congress to act. The 1985 farm bill – The Food Security Act of 1985 (PL99-198) — rolled backed interest rates on all RDLF loans to the rate when the loan was made. For the loans made in 1980 and 1981, this meant an interest rate of only 1% for the 30 year term of the loan. This construct left the note rate for 1983 loans unchanged. The farm bill also transferred the RDLF from HHS to USDA and its Farmers Home Administration (FmHA).

Persuaded that a program like the RDLF had potential for improving rural economies, Congress included a provision in the 1986 Human Services Act (PL 99-425) that set the interest rate on all RDLF loans – including those made in 1983 – at 1%, and gave the Secretary of Agriculture authority to make future loans under terms and condition established in the both the Reconciliation Act and the Human Services.

The Fiscal Year 1988 Agriculture Appropriations Act (100-202) provided $14 million under the RDLF authority. FmHA drafted a rule for a new program – the Intermediary Relending Program (IRP).

Today, USDA makes one percent, thirty-year loans to qualified intermediaries. The Intermediaries in turn use the loans to capitalize revolving loan funds that target the needs of small and emerging rural businesses in the intermediaries’ service area.

What is an Intermediary’s Role?

IRP intermediaries are responsible for marketing and administering a revolving loan fund. They use IRP funds to leverage additional public and private investments for its business borrowers. Intermediaries are limited to lending up to the lesser of $250,000.00 or seventy-five percent of the total cost of a borrower’s project per qualified borrower.

What is the Application Process?

The IPR application process is competitive and made up of five required parts: (1) a written work plan; (2) plan for how to leverage additional financing for businesses; (3) marketing plans; (4) proposed interest rates; and (5) detailed goals and benchmarks that the intermediary plans to meet. A key requirement is the match: in order to be competitive an applicant must commit to making an equity contribution of at least 25% of the total requested.

USDA reviews applications on a quarterly basis; however money is not dispersed evenly per quarter. USDA originates 40 percent of funds in the first quarter, 30 percent in the second quarter, 20 percent in the third quarter, and 10 percent in the fourth quarter.

How are Applications Scored?

The scoring requirements for the IRP program are detailed in 7 C.F.R. 4274.344, which provides specific point values to certain factors, such as the intermediary’s loan priorities, including the amount of non-federal fund the intermediary will use, and the median household income for the service area, which USDA deems important. The highest point value that an intermediary can receive is for contributing 25% or more to the IRP revolving loan fund (50 points.) The next highest point value is 30 points (based on contribution to the revolving loan fund or years of experience). Most criteria are valued between only 5 and 15 points.

What are the Area Requirements?

Eligible areas for IRP funding are rural areas which are outside of a city or town with a population of less than 50,000. Thus, urbanized areas near a city with a population of 50,000 or more are not eligible. Under current rules, a service area for an IRP is limited to 14 counties.

How can a Borrower use IRP Funds?

The ultimate recipient of a loan from an IRP intermediary can be used for a wide variety of purposes, including for the acquisition, construction, conversion, enlargement, or repair of a business or business facility, purchasing land or equipment, developing land, transportation services, or start-up costs.

IRP by the Numbers

- 1% – the fixed interest rate of IRP funds to intermediaries

- 30 years – the maximum loan term

- 3 years – the number of years an IRP intermediary is permitted to make interest-only payments

- 52 – the number of states (including Puerto Rico and the Republic of Palau) with IRP loans

- 1,020 – the total number of loans issued to IRP Intermediaries (1984 – March 2014)

- 492 – the number of organizations that have served as IRP Intermediaries

- 9,000 the estimated number of rural businesses who have received financing through the IRP

- 7-to-1 – the amount of private dollars leveraged per $1.00 in IRP funding

- $100,000.00 – the average size of a loan to an IRP borrower

- $747,226,497.57 – total amount of IRP loans issued to intermediaries (1984 – March 2014)

Source: USDA data – March 2014

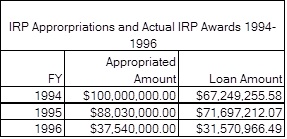

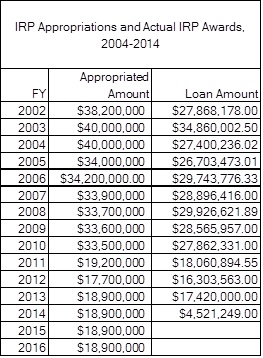

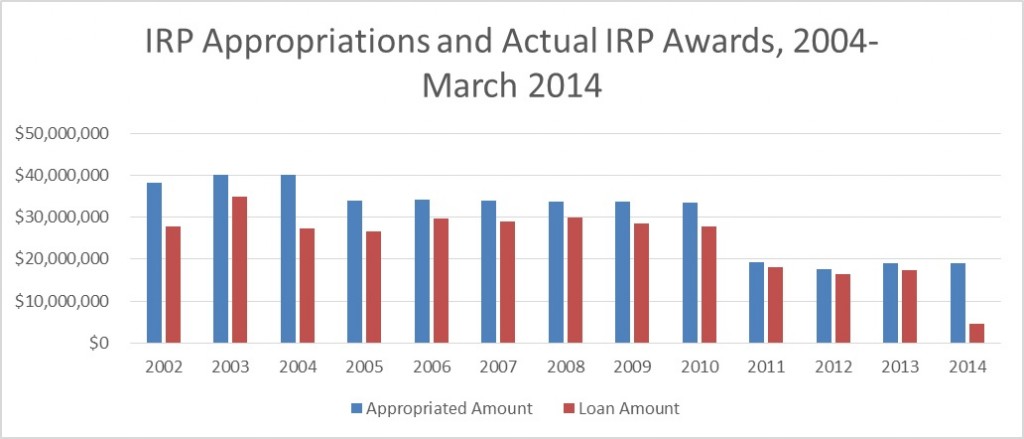

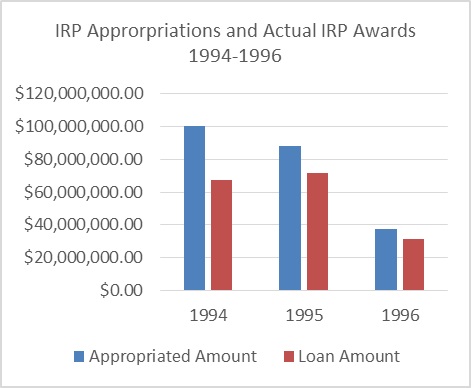

Appropriations for IRP

Appropriations for the IRP have suffered the same fate as other federal community development programs. Over the 35 years, federal community development spending at HUD, Commerce, Interior and USDA as measure as a share of GDP has fallen by 75%. For the IRP, the high-water mark of appropriations was FY 1994, where $100 million was appropriated.

Today, IRP appropriations stand at nearly $19 million.

How to Improve the IRP

Key Recommendations

- Revise the current rule — The last full re-write of the IPR was in 1994. The world of development finance has changed over the last 20 years. The last change in procedures, as opposed to regulations, was made in 1993. The principal result of that was the use of IRP funds in participations. However, most of the impediments to a 21st Century IRP are imbedded in the regulations governing the program;

- Increase Loan Limits — The current cap on IRP lending has been in place since 1994 and stands at $250,000. If that cap were adjusted for inflation, the limit would be $401,000. Even before the current economic downturn, the IRP was one of few sources of fixed rate financing in rural areas. Now, with many private financial institutions pulling back, IRP is a key source of fixed rate credit for rural businesses. For deals needing more than $250,000 multiple IRP intermediaries to lend to the same deal. USDA should eliminate the loan cap or, failing that, raise that cap on IRP loans to $5 million, which is the limit on SBA (7) (a) guarantees. Alternatively, if the cap is raised to the inflation adjusted rate of $401,000, then it should be adjusted annually thereafter;

- Eliminate the 14 County Rule — Under current USDA instructions, an intermediary a service area for the IRP may not exceed 14 counties. After the IRP loan is revolved, the intermediary may use the funds beyond the 14 county limit. This artificial limitation does not result in better deals – successful applicants must score well on a variety of measures designed to ensure that IRP is low income communities and jobs are going to people who need them. The rationale behind the limitation is community accountability. However, other federal agencies have founds was to ensure that targeted communities or populations are represented on boards or advisory committees without capping the geography served. The current limit slows the initial obligation process and does little to create long term accountability;

- Revise the Intermediary Equity Contribution — In order to be successful in getting an IRP loan, under current regulations an intermediary must make an equity contribution to the IRP revolving fund of at least 25% of the federal loan. While the loan, along with interest is paid back over the 30 year term, the intermediary’s equity must remain in the fund until the loan matures. This requirement should be revised so the intermediary’ equity is returned as they loan amortizes;

- Establish a Preferred Lender Program — Many of the intermediaries in the IRP program have long borrowed money from USDA – some for more than 30 years. These high performing organizations have not only improved rural economies and provided financing to businesses and projects, they protected the government’s interest. However, with limited funds and great demand, intermediaries often apply for more loan capital as soon as the moratorium period on their most current loan expires. The preferred lender program would provide a performance based incentive to intermediaries that satisfy selected targeting criteria and allow intermediaries to retain their capital in return for meeting certain performance criteria. USDA would grant certain qualified intermediaries a moratorium on principal and interest payments to USDA as long as targeting criteria is satisfied and IRP funds are on a sound financial footing;

- Take More Aggressive Measures on Unobligated IRP Fund — with limited appropriations, the notion that millions of dollars of IRP funds are unobligated is a cause for concern. Everyone agrees that rural businesses have few options to obtain credit on reasonable rates and terms. Everyone also agrees that the business climate not just in rural America but all over the country has been challenging for several years. For these reasons USDA should provide technical assistance to intermediaries that have encountered difficulty in administering IRP fund. USDA should take more aggressive measures to require non-performing borrowers to turn over their funds to other intermediaries;

- Limit USDA Review of Administrative Budgets — in at least some cases USDA is objecting to budget submissions that do not reflect a positive net fund income. This is not a requirement of law or regulation but instead State Office policy aimed at maintaining a loan fund after the IRP loan is repaid. This requirement is not a function of the repayment ability or record of the intermediary and is almost always of a result of one expense – repayment of principal – outstripping interest income. In any event principal repayments are not an expense to be accounted for in determining self- sufficiency of the program The National Office should notify State Offices that maintaining a positive net fund income is not a requirement when applied for the purpose of capitalizing a fund;

- Permit Segregated Bank Accounts — IRP rules require separate bank accounts, segregation of income earned on I RP funds and keeping deposits within FDIC deposit insurance requirements. IRP intermediaries that have several federal sources, including other RD sources, face similar but not identical requirements. USDA should allow intermediaries to pool all federal income in a single account and subaccounts could account for specific sources. USDA should provide consider flexibility of deposits beyond FDIC limits and approve our conservative investment plans for this purpose. IRP also requires segregation of matching funds and that all income earned from matching funds be returned to IRP lending pool. USDA should allow pooling of all federal sources and required matching funds.

Case Studies

Maine

Coastal Enterprises, Inc. (CEI) used IRP funds for a loan to the New England Outdoor Center in Millinocket. The business is a previous CEI borrower. It is one of the preeminent examples of an innovative nature-based tourism and recreation business in rural Maine. The business is committed to preserving shoreline and natural lands as public space. It began in 1982 and offers rental cabins, whitewater excursions, educational programming, an upscale restaurant/lounge, and related activities. It offers 17 high-end, fully equipped cabins for rent with frontage on Millinocket Lake and spectacular views of Mt. Katahdin, Maine’s tallest mountain. The business has 22 full-time year round and 18 seasonal employees.

New England Outdoor Center fits squarely into the goals of CEI’s five year Platform for Sustainable Lending and Investment, which prioritizes nature-based tourism and recreation and builds on its past investment of $15 million in 170 businesses in the industry, with another $40 million in private leverage. As we begin the fourth year of our 5-year strategy, CEI has already exceeded its 5-year sector investment goals by 53%.

California

In Paradise, California, Rural Community Assistance Program of Sacramento, used IRP funds in the amount of $83,210 were used to help repay a short term bank loan and allow the planning for a residential and community center to continue. The borrower, Paradise Youth and Family Center, is a nonprofit organization, with primary members being the Town of Paradise, Youth for Change, Paradise Ridge Youth Soccer Club and Community Housing Improvement Corporation. The project, when completed, is planned to have residential housing (both single and multifamily), a gym/community center, a Boys and Girls Club, a Middle School, a Skate Park, open spaces and a wetland reserve in a phased development of 48.38 acres. Additionally, a 36 unit Low Income Housing Tax Credit project has been constructed and is fully occupied.

Washington

IRP funds in the amount of $39,116 will be used by the Campbell’s Glen Homeowners’ Association to provide updated arsenic removal treatment for a small 28 user water system in Clinton, Washington. The existing small system had installed water treatment equipment several years ago, and while that treatment equipment had successfully dealt with some water issues, it had not consistently lowered the arsenic levels within drinking water standards. The IRP funds will be used to bring the system into compliance with Washington State Department of Health requirements for allowable arsenic levels in drinking water. Additionally, the funds will also address odor and discoloration issues.

Minnesota

Although the former National Guard Armory, in Park Rapids, Minnesota, is one of the most prominent buildings in the downtown business district, it sat abandoned and unused for almost 20 years. The property was considered “incurably obsolete” when purchased for redevelopment by a summer resident of this lakeside tourist community, however that resident saw the potential that the property had to be redeveloped into a profitable site. Thanks to funding from the Midwest Minnesota Community Development Corporation (MMCDC), which provided total financing of $475,000 in 2010 to support the first phase of the project, a 6,000-square-foot redevelopment resulting in a new restaurant and one retail tenant and 12 permanent full-time jobs. This 24,000 square-foot historic landmark is now scheduled for complete redevelopment as a key strategic anchor as part of a comprehensive downtown redevelopment plan adopted by the City of Park Rapids.

MMCDC utilized alternative funding sources, including from the Office of Community Services and the Minnesota Historical Society in its first phase. Once complete, the integrated mixed use Armory Square facility will feature a 200 to 300-seat performing arts venue, conference space, events center, and an art gallery under the banner of the Upper Mississippi Center for the Arts. In November of 2012 the Armory Square redevelopment project received a Minnesota ReScape Community Impact Award, and was recognized as an exemplary model for redevelopment of a distressed brownfield site.

Midwest Minnesota Community Development Corporation is a leading provider of community economic development services to underserved communities in Minnesota, with a particular focus on rural areas.

January, 2016